Plug-In Solar: Banned Today, Legal Tomorrow?

By Gordon Routledge

Sunday 11th January 2026

SHARE IT

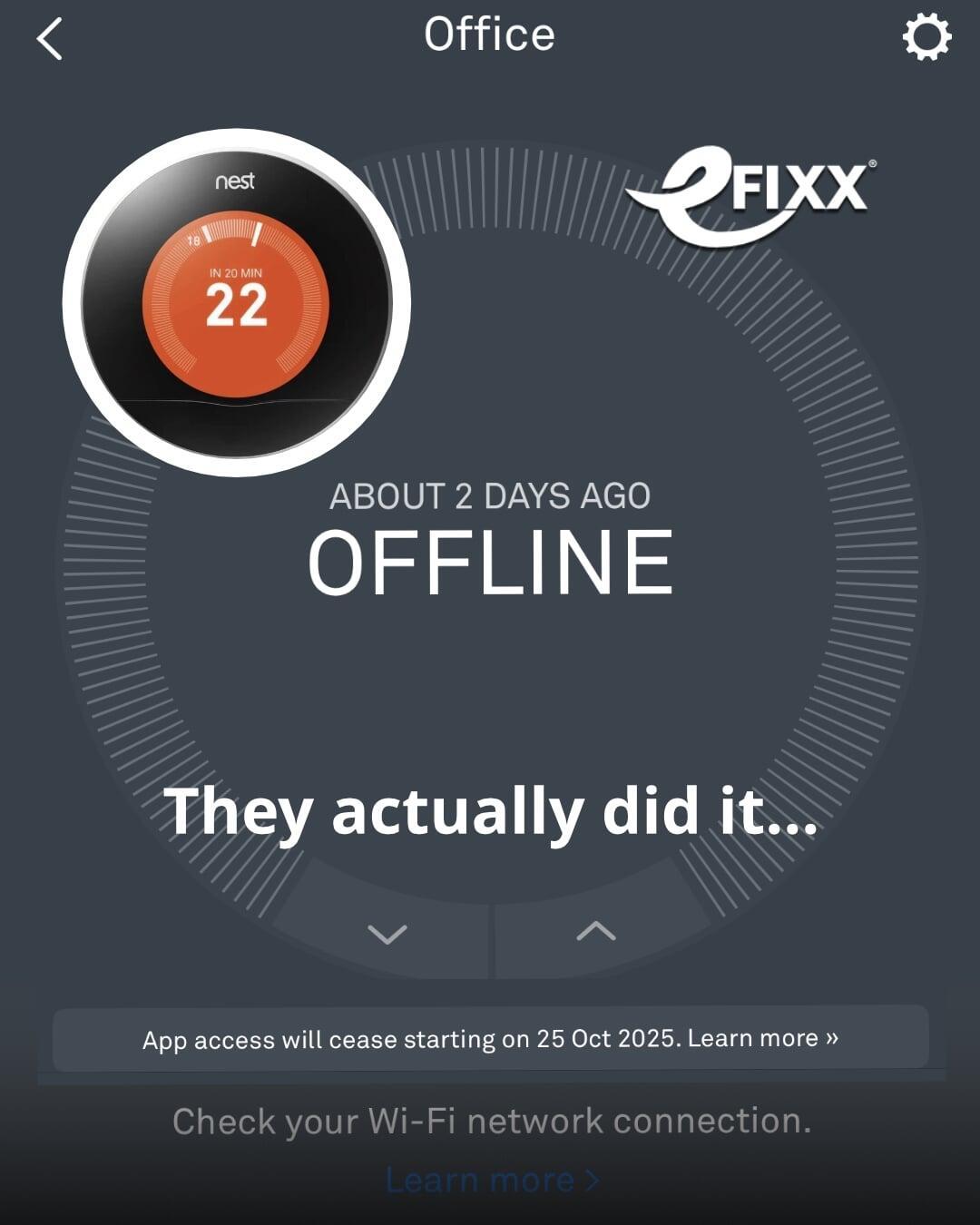

For a long time, “plug-in solar” has sounded like one of those ideas that works on the continent but will never fly here. Panels on a balcony or shed, a micro-inverter, then a lead straight into a standard socket; simple, cheap, and wildly attractive to renters and flat-dwellers who can’t get rooftop PV.

In the UK, though, the official position has effectively been: not allowed.

What’s changed is that the government has stopped treating plug-in solar as a fringe curiosity and started treating it like a policy problem to solve, and we can see that shift clearly in black and white.

In the UK, though, the official position has effectively been: not allowed.

What’s changed is that the government has stopped treating plug-in solar as a fringe curiosity and started treating it like a policy problem to solve, and we can see that shift clearly in black and white.

The UK Has Started Moving

On 30 June 2025, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) published its “solar drive” update and explicitly said it was setting out steps to make plug-in solar available in the UK, describing it as portable solar connected directly into plug sockets and flagging it as ideal for apartments with balconies. In the same announcement, DESNZ also stated plainly that plug-in solar is currently unavailable in the UK due to longstanding regulations.

Not long after, that intent moved from talk to tenders. DESNZ published a tender notice for a “Plug-in Solar PV Study” on the government’s Find a Tender service on 31 July 2025. The brief is very direct: assess whether plug-in solar PV connected to certified inverters can be safely deployed in the UK without socket or building wiring modifications, covering the technical, regulatory and practical feasibility, and producing clear recommendations. The tender set an estimated contract value of £90,000.

Then came the key moment: the contract award. On 20 October 2025, DESNZ published the award notice confirming the supplier as Arceio Limited, with a contract value of £80,309. The same notice also set out the expected delivery window: 31 October 2025 to 27 February 2026, with an option to extend to 30 April 2026.

So if you’re wondering whether plug-in solar is really on the UK’s radar, it is. We’ve gone from a June 2025 policy signal, to a summer tender, to a named supplier and a paid-for study scheduled to report in early 2026.

What is Plug-In Solar?

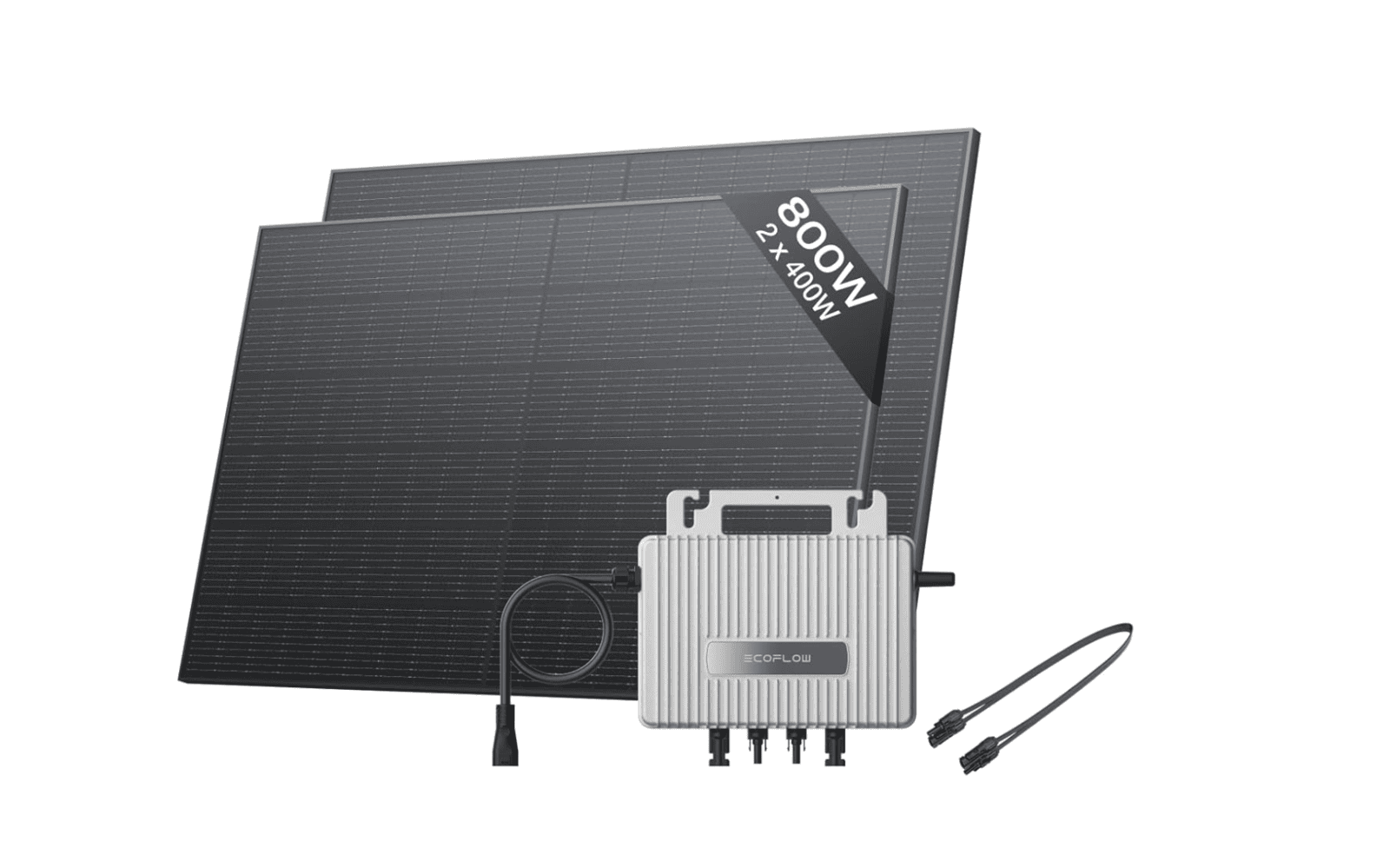

Plug-in solar is the small-scale, DIY-friendly end of grid-tied PV: usually one or two PV panels paired with a micro-inverter, designed so the AC output can be connected into a home’s electrical installation via a plug. You’ll see it marketed under a few interchangeable names: plug-in solar, DIY solar, and most commonly balcony solar. In Germany it’s known as a “Balkonkraftwerk”, literally a balcony power plant.

In simple terms, it works by synchronising with the mains and offsetting whatever the property is using at that moment, so it tends to cover base loads first: fridge, router, standby loads. These systems are typically kept small, and across Europe the headline limit you’ll often see is around 800 watts, which is why most kits are marketed in that ballpark.

Germany is the big proof point that it can scale. By June 2025, figures based on Germany’s official register put plug-in systems at over one million recorded installations, which is exactly why other countries are watching closely.

That experience is now being adopted elsewhere, notably Belgium. From 17 April 2025, Belgium allowed plug-in solar (and plug-in batteries) under a formal set of conditions: the equipment must be approved, systems must be properly notified and registered, and the installation process includes an inspection of the electrical installation by a recognised inspection body as part of the grid connection paperwork. In other words, legal, yes, but definitely not a free-for-all.

We tested a plug-in battery — here’s what actually happens.

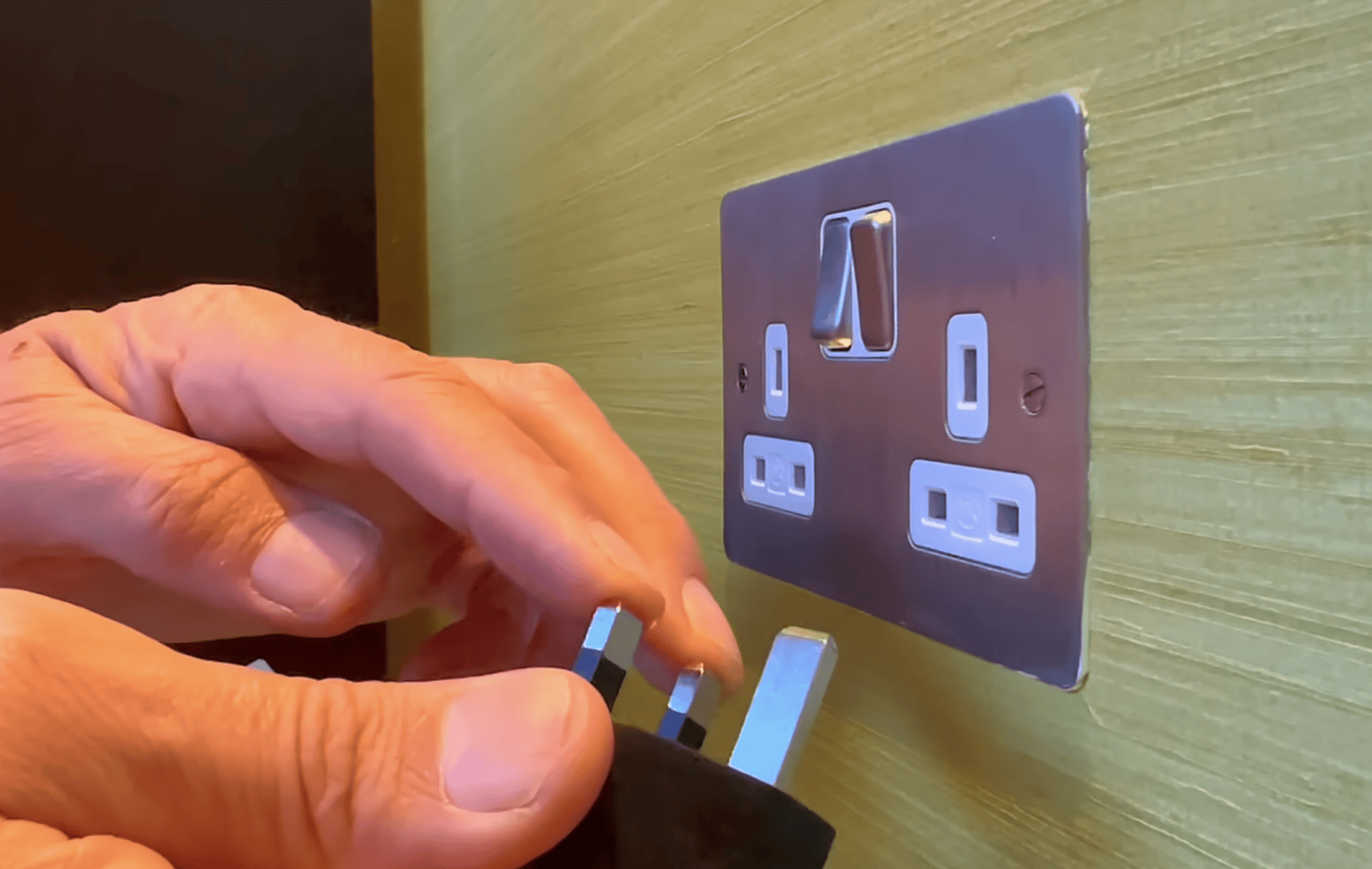

UK Barrier 1: The Plug, the Socket, and Human Behaviour

The first barrier is conceptual, and it’s the one that makes most sparks wince: sending power “the wrong way” through a 13A plug. In theory, if you unplug a plug-in solar inverter while it’s generating, you might imagine the pins staying live. That’s the nightmare scenario people jump to.

In the real world, that isn’t how compliant grid-tied inverters behave. Loss of mains equals shutdown. The moment the inverter detects the supply has gone, it’s designed to stop exporting rapidly (anti-islanding). We even proved the principle ourselves during our video review of the DJI Power 2000 plug-in battery: disconnect the supply and the export stops, so you don’t end up with a “live plug” situation.

The real safety debate isn’t whether modern inverters can do this, it’s whether every product that ends up in people’s homes will do it reliably, every time, under real-world conditions.

Then there’s the UK’s bigger wrinkle: our sockets and our habits are different.

Across much of mainland Europe, 16A radial circuits are the norm, and the common plug system is Schuko, typically paired with single sockets (one outlet per accessory). That naturally limits how much “stuff” gets piled onto one point of connection. In the UK we’ve got the 13A fused plug, usually connected to a 32A ring final circuit, and we strongly favour double sockets as the default outlet.

In simple terms, plug-in solar changes what a socket might be asked to handle. It’s no longer just “a load plugged in”, it can become a point where generation and consumption overlap. A homeowner could have the inverter on one side of a double socket and something hefty on the other, a 2kW kettle being the obvious example. On paper, the circuit might be fine, but the weak link is often the accessory itself: the contacts, terminals, and the real-world condition of that socket and its terminations.

That’s also why UK safety experts focus on behaviour, not just ratings. People will stack things. They’ll use adaptors. They’ll plug two inverters into the same double socket. And while even 2 × ~800W is only about 1.6kW, the concern isn’t the headline wattage. It’s the messy reality of older sockets, tired connections, and long-duration heat build-up that turns “within spec” into “cooked terminals”.

And we’ve already seen a near-perfect cautionary tale: “granny charging” EVs from 13A sockets. In principle, that should be done only on a suitable circuit and a properly rated accessory, but plenty of people ignore that, and the internet is full of photos of overheated, toasted sockets from long-duration EV charging. That’s exactly the collision UK regulators are worried about with plug-in solar: not the technology in isolation, but what happens when it meets the way UK homes are actually used.

Finally, there’s the approvals piece. If an inverter is going to connect in parallel with the LV network at microgeneration levels, G98 is the framework it typically sits under, and the industry now uses ENA Connect Direct to list and track devices and applications. The key point is this: plenty of small inverters in the UK ecosystem already operate in the same power territory as the “800W class” kits being sold in Europe, and many products in that bracket are already easily available online.

And here’s the kicker: whether the UK approves plug-in solar or not, the hardware is already landing in people’s baskets. Search Amazon UK and you’ll find plug-in micro-inverters and balcony solar kits being marketed to consumers today, which means the UK isn’t deciding whether the products exist, it’s deciding whether we end up with a regulated route, or a grey-market bodge-fest.

UK Barrier 2: RCDs and the Bi-Directional Problem

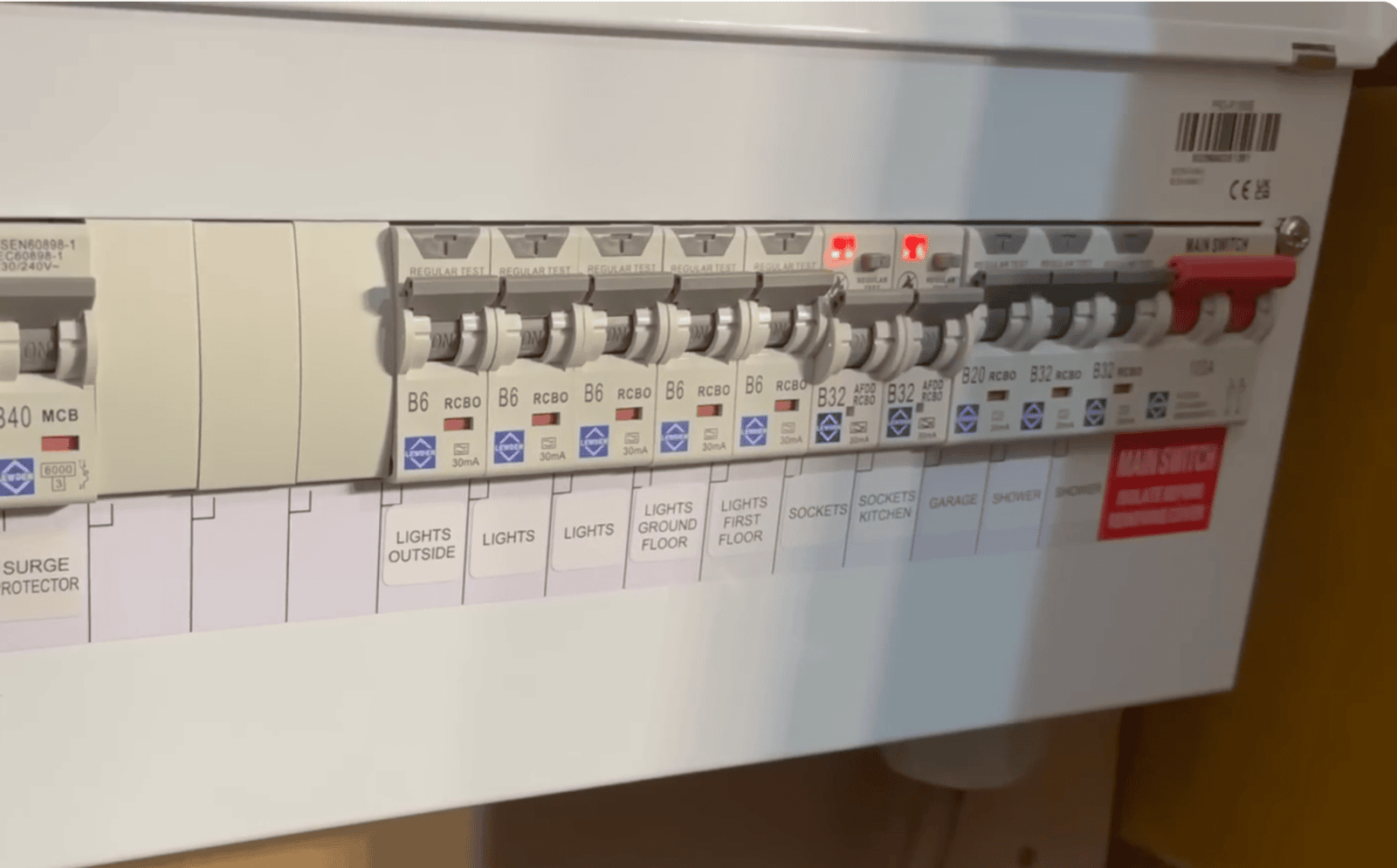

The next big headache is RCD behaviour when power can flow both ways. BS 7671 has now formally acknowledged that modern homes aren’t just loads anymore, they’re becoming sources as well. Amendment 3 introduced the idea of bidirectional protective devices and requires designers to consider whether protective devices are suitable when supply can be connected at either set of terminals.

The worry is simple. A lot of protective devices were historically treated as line-in, load-out. Put power in the “wrong” side and you can get nuisance behaviour, incorrect operation, or in the worst case, damage. That’s exactly why the bidirectional conversation exists at all.

Layer that onto the reality of UK housing stock. A huge proportion of homes are still on split-load boards with Type AC RCDs protecting multiple circuits. BS 7671 is clear that Type AC devices are only suitable for pure sinusoidal residual current, and that DC components from modern electronic equipment can blind them. In other words, the average domestic setup many plug-in solar kits would connect to is already not aligned with the direction of travel in the regs, even before you add generation via a socket.

That’s why plug-in solar feels, to many UK engineers, like it cuts straight across the logic of recent Wiring Regulations updates. We’ve tightened up on device suitability, DC leakage risk, and bidirectional power flow, and then we’re discussing letting the public export energy via whichever socket happens to be nearest the patio doors.

The uncomfortable question is whether this is actually unique to the UK. Germany and Belgium have moved ahead with plug-in PV in large numbers and are dealing with the same fundamental physics. So if the UK does decide to legalise plug-in solar, does that force the IET to take another look at how the regs apply in a plug-in microgeneration world?

UK Barrier 3: Battery Storage and Where It’s Allowed to Live

One reason this conversation gets complicated in the UK is that we’re actually ahead in one key area: dynamic energy tariffs. For many households, the goal isn’t exporting a few hundred watts back to the grid, it’s keeping that energy on site. That’s why so many residential PV installs here are now paired with battery storage, soaking up surplus generation in the day and using it later at peak times.

Plug-in and balcony solar doesn’t escape that trend. In other markets you’ll already find systems sold as panel plus micro-inverter plus storage, or modular setups where batteries can be added later. We’re seeing the same category creep into the UK too, not least with plug-in battery products like the DJI Power 2000, which we reviewed recently.

The catch is that adding batteries introduces another UK-specific barrier: fire safety guidance and battery location. PAS 63100 has pushed the industry away from the old “stick it in the loft” habit. The direction of travel is clear: avoid lofts, avoid escape routes, and where practicable, position batteries in a suitable external location.

So even if plug-in solar itself can be made acceptable, the moment it’s bundled with storage it collides with another reality of UK housing: there aren’t many perfect battery locations. That’s a big practical hurdle for the very people balcony solar is meant to help.

The Bit Everyone’s Missing: This Could Actually Help

It’s going to be genuinely interesting to see what drops out of the DESNZ safety study, because this isn’t just a regs argument, it’s an access problem. Proper rooftop PV is brilliant if you’ve got a roof you’re allowed to touch, the budget to do it properly, and the right setup to make it pay. If you’re renting, in a flat, or locked out by cost or circumstance, you can be excluded entirely.

That’s where plug-in solar could be a rare thing in energy policy: a small, simple change that helps the people who need it most. We’re not talking about turning Britain into one giant balcony-mounted power station. We’re talking about modest generation that chips away at daytime consumption, the sort of saving that actually matters when money is tight.

And if it does get approved, you can almost see what happens next. Britain has a proud tradition of adopting successful European ideas eventually. Germany has already made balcony solar mainstream, so don’t be surprised if the next great German import turns up in the most British way possible: the middle aisle of Aldi. You know the one. You go in for milk and come out with a paddle board, a MIG welder, and now… apparently… a plug-in solar kit.

I’m Testing It So You Don’t Have To

In the meantime, I’m not just watching this story, I’m living it. I’m currently renting, so I’ve decided to test the sort of setup you’re not meant to do in the UK right now. As I’m writing this, I’m sat in my living room next to 6kWh of plug-in battery storage, a plug-in micro-inverter, and I’ve got two panels landing this week.

So yes, today it’s still in that awkward “not allowed” territory. But if the UK is serious about widening access to solar, it might not stay that way for long.

Stay tuned.

SHARE IT

CURRENT THINKING

V2G: The Vicar’s Wife Drove it; Now it Runs Your House.

The term game changer gets thrown around like confetti, but with vehicle to grid (V2G) it’s deserved. Your EV is a battery on wheels. With a compatible car and the right charger, vehicle to grid (V2G) will run your home, support the grid, and might even boil the neighbour’s kettle.